Metabolic Flexibility

Featuring

Nasha Winters, ND, FABNO

WATCH

LISTEN

READ

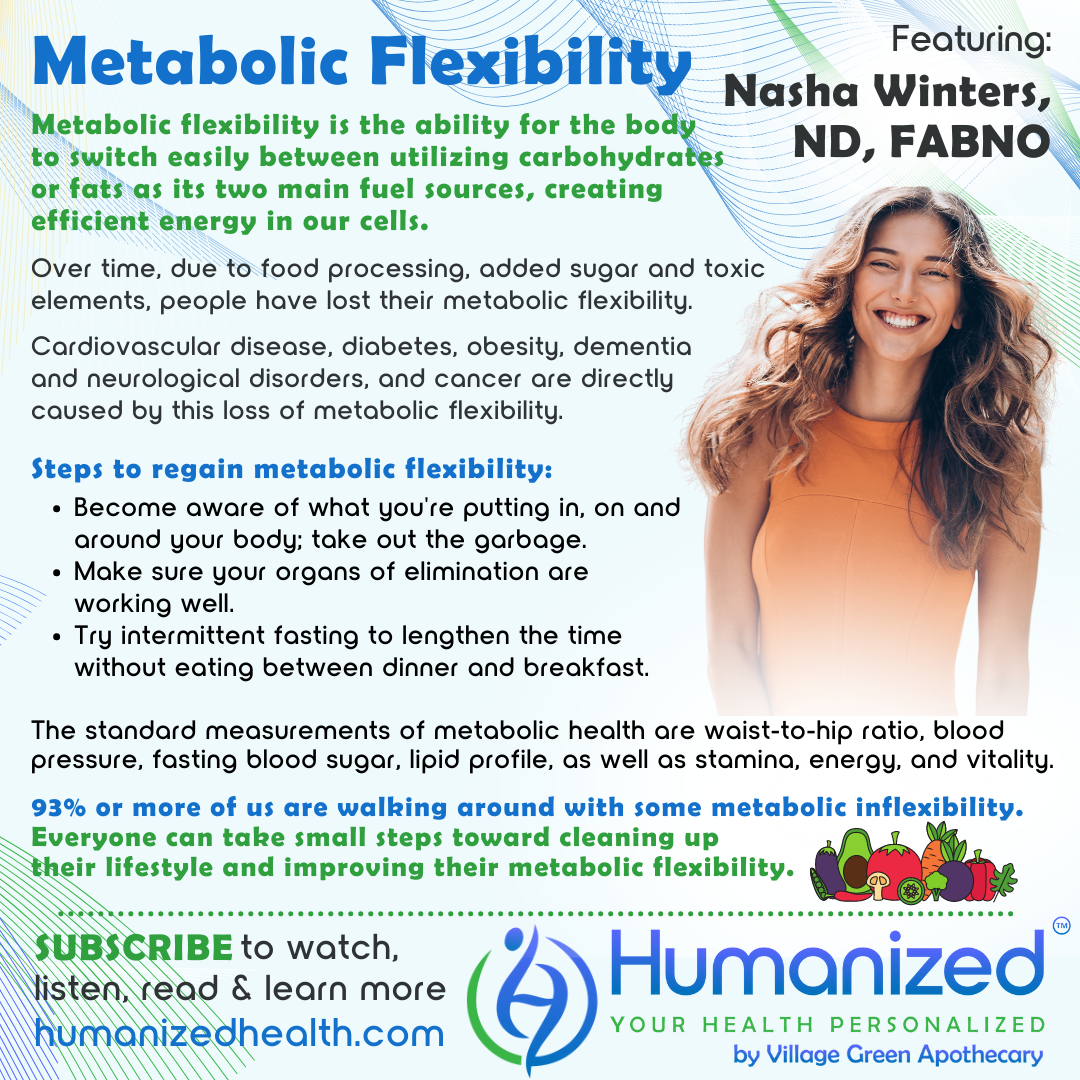

David Stouder: Welcome to the Humanized podcast, and it’s all about personalizing your health. I’m your host today, Dave Stouter. Now, today we’ll be discussing an interesting topic. I was thinking back and I’ve been in the industry a long time. I work at Village Green Apothecary, who is our main sponsor, with a lot of certified nutritionists and pretty smart people, and I cannot remember ever hearing the concept of metabolic flexibility. Now, maybe it came across sometime, but I don’t remember it. And we’re going to talk about metabolic flexibility, I bet it’s new to you as well, with Dr. Nasha Winters. Now, before I introduce her, I want to remind you that you can subscribe and get all, we have a whole bunch of video, audio and transcripts for free, of all these things. So please tune in to HumanizedHealth.com. And again, I want to thank our lead sponsor, Village Green Apothecary, for making this possible. And you can go visit Village Green at MyVillageGreen.com.

Now, let me tell you, we’ve done some great podcasts with our guest today, Dr. Nasha Winters, and I would urge you to go back and look at some of them. She has been on a personal journey with cancer for the last 30 years. Her quest to save her own life transformed into a mission to support others on a similar journey. From survivor to physician and from physician to mentor, Dr. Nasha is teaching physicians and practitioners how to treat cancer with an integrative approach that focuses on the patient and not the tumor. Imagine that. Now, Dr. Nasha Winters is on a mission to build the first inpatient integrative facility, focusing on the terrain-based metabolic approach to cancer treatment.

So there’s that word, metabolic. And, Dr. Winters, welcome to the Humanized podcast.

Nasha Winters: It is always great to be with you guys. So thanks, David, for having me. And I love that this is the topic today and that it’s sort of new to you and perhaps to many of your listeners.

David Stouder: So let’s start. It probably is. So what exactly do you mean by the term metabolic flexibility?

Nasha Winters: So, not that long ago – what, 150 years, 175 years ago – we were all like hybrids. Okay, we were all like human Prius [laughs]. We were able to easily, without effort, without trying, we were able to move in and out of burning different energy sources, depending on the resources in and around us. And so what happened though, is about 1850s, when we moved into the industrial food revolution, we started to change that ability. We started to basically put the brick on the accelerator pedal to really only easily burn one fuel source, unless we come in with a stronger intervention, to change that.

And these two energy sources – what we did naturally and what we’re stuck in today – were the energy sources for our cells to make the very energy that keeps us going every day, and to do all kinds of biochemical processes in our body, and to protect our genome, and other things. These two fuel sources are simply carbohydrates as the main fuel source, or fat as the main fuel source. And we were able, because of different seasons and different regions and different climates and different availability and accessibility, we were having times of the year where we were more carbohydrate rich and more carbohydrate restricted, depending on our environment. We were getting more and more, building up our carbohydrate intake since the industrial food revolution, as suddenly these types of food groups became more and more accessible to us all the time, thanks to the milling processes. So we started to mill sugar and flour, we started to add it to everything. You started to have people shipping. We had refrigeration that came shortly after that. We started to be able to contain and ship and store and process things in a way that made it very carbohydrate dense. So just to give you context, in the 1850s, the average human, okay, the average human took in 5 pounds of sugar per person per year. David, what do you think today’s average sugar intake is? Do you have any guesses?

David Stouder: I’m going to say 150.

Nasha Winters: That’s a really close guess. Some studies say as little as 145, but as much as 175 pounds of sugar per person per year.

David Stouder: Yikes.

Nasha Winters: Right? And it happened in really, when you think about it, in just a few generations. So that’s a big, big change. And what happened is our bodies have forgotten how to be that hybrid engine. And what that has led to is a metabolic instability and inflexibility. So we are stuck only being able to process one form of nutrition easily and effectively, and we will default to that readily without specific input by us.

David Stouder: Wow. Now this next question, I mean, all kinds of sort of awful endpoints are going through my brain right now, but, so what’s the risks associated with the fact that we’ve given ourselves so many easy carbohydrates for so long and enough generations that, like you said, we only want to burn carbs and it can really be an effort for most of us to burn fat properly? I mean, I’m sure everybody out there probably has some of their own answers, but what’s the consequences of this?

Nasha Winters: It’s a really good question, because those consequences are what we see day in, day out today. This is what is bankrupting our medical systems. This is what is setting us up for vulnerabilities to global pandemics. This is what is setting us up to have the top five deaths that we experience as humans caused directly by this loss of metabolic flexibility. So things like cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, dementia and neurological disorders, and cancer are the big five that we die of and from today. And those are directly related to that energy being either efficient and effective, or being inefficient and aberrant. And so you can imagine that the teeter-totter is pushing us more and more into the aberrant side of things.

David Stouder: So let me ask you a question. I mean, I’ve met people, I’m sure we all know people who seem to have a tremendous problem with carbohydrates, sugars and weight gain, and the problems you just mentioned, and other people seem to maybe have retained their flexibility, at least for the moment that we may see them. So again, I think I know some of the answers to this, but what do we do to push ourselves firmly into this inflexibility?

Nasha Winters: Well, let’s start with this, in that, you’re right, that you can kind of look around the world today. When I think 67% of us are morbidly obese today, and over 75% of us… like, 75% are obese, 67% of that are morbidly obese, meaning over a 30 to 35% body fat. That right there is something you can visually see. But the other growing condition that we don’t see is something known as TOFI – thin on the outside, fat on the inside. TOFI.

So even if you look on a certain way, walking around this planet, you can confuse it yourself, to think that “I’m fine. Look at me. I can eat anything I want, and I’m still looking fit.” That is no longer as healthy as we once thought. Once we looked under the hood a little deeper, there was a growing condition today known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, NASH, or in a non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, that’s the other, NAFLD. These are the names that are coming out here. And we’re now seeing this in our 8-year-olds, our 9-year-olds. Pre-menarche, little girls, teenagers, young adults, no matter what their physical body composition looks like, it’s already showing up and giving us clues that there’s some metabolic instability.

So that diet we just talked about, of the changes from 5 to 175 pounds of sugar per year, that’s one of the instigators. The other instigator of this is also the type of sugar. So when we started to process it back in the ’60s and ’70s, we also started to put into the market high-fructose corn syrup, which is made from corn. Okay. And it is gone through, in a process to be created, by utilizing something that actually contains mercury. So we now have these mercury, metallo-estrogens. It is crazy because it also then adds insult to injury because it pulls all kinds of other levers – not just the toxicities to our liver themselves, but also endocrine disruption.

And so that’s a key word here because your listeners, I’m sure you’ve had people talk about endocrine disruption, but the big things that are changing the way our body processes our nutrients, it processes whether we burn sugar or fat, are things coming from our environment around us. So anything we’re putting in, on and around our bodies, such as the body care products – most of us are putting dozens of those products on our skin every single day before we even walk out of the house to go to work in the morning. Many of us are eating foods that are filled with these chemicalized components. Many of us are breathing air or drinking water or ingesting foods that were grown in soil that are contaminated with these things. And those things come from things like plasticizers. Do you remember the movie, the 1960s movie, The Graduate?

David Stouder: Oh, yeah.

Nasha Winters: And so there’s a very specific scene in that movie when he’s like, what should I invest in in the future? And he is like, invest in plastics, they’re the wave of the future! So when you think about, that’s like a moment, like a stamp in our time, of pre-Graduate movie to after, of things changed drastically after that, as we started to introduce and invest in all of these plastics that are now almost difficult to avoid, and ubiquitous into our environment.

David Stouder: Well, I remember early on working in health food stores in the ’70s where we were promoting plastic to save the trees.

Nasha Winters: Exactly.

David Stouder: And then all of a sudden we’re like, what do we do with all these plastic bags?

So, the idea of TOFI, that’s interesting. But I have met people who were slender and appeared to be fit, but like you say, fatty liver, you can still have fat issues based on this.

So now, we look at people who… let’s just look at the weight section a moment, because typically when your metabolism gets out of hand and you’re burning too many carbs, most of us will put on some weight, as you said, either overweight or morbidly obese. But people find different ways to lose weight and then they seem to gain weight, which is almost like they sort of forced the issue, but they didn’t change the fundamental thing, like you can sort of, whatever – you can starve yourself and maybe lose weight, or you can do this and that. Once you’ve sort of disrupted yourself there and you’ve become inflexible, is it possible to retrain to where you really get that flexibility back?

Nasha Winters: Absolutely. Absolutely. That’s the thing that I think we’re taught. We’re sort of like taught that it’s not possible, that it’s not possible without either eating, like restricting yourself even further, or working out even harder. Because what the doctor’s advice is, is typically eat better, exercise more. But when you’re swimming in this pool of these ubiquitous endocrine disruptors that are pulling all kinds of levers impacting hormonal communication, such as leptin and ghrelin, which are things that make us hungry or satiated, if they’re impacting things like our insulin, which is what’s storing body fat in our body, if it’s interrupting our prolactin levels or our melatonin levels, our sleep and circadian rhythm levels, we start to realize that every one of our hormones are sensitive – not so much to being hormone deficient, but to this change in our diet and into these endocrine disruptors, which are jamming the work.

So people think, well, if I just take hormones, I’ll fix the problem. Or if I just exercise more, I’ll fix the problem. But what we need to do is we need to take out the garbage first. That’s our first step. The first step is to become aware of what you’re putting in, on and around your body. So there’s number one. A lot of industries and a lot of people go out of their way to keep you from knowing that information.

It’s very easy to go on IARC [International Agency for Research on Cancer] or some of these other third-party research institutions that tell you what are known carcinogens, that tell you what’s in your drinking water, such as the EWG, which stands for Environmental Working Group dot org, put in your zip code, see what’s in your water. Take a look at what you’re eating your food in, drinking your water out of, storing your food in. If there’s plastics touching it, you are touching it. The average person today is eating a credit card per year of plastics that are just coming out of your sea salt, for instance.

So we’re definitely taking these things in, plus the body care products, plus the glyphosate, which is the Roundup spraying all of our crops. All of these are endocrine disruptors. So if you’re eating foods that are highly processed, you are getting glyphosate. If you’re eating foods that are grains and legumes, even organic, they sequester glyphosate. So you’re still getting residues of that, even when you’re doing your best to avoid it. If you are still using commercial body care cleaning products and commercial lotions and shampoos, you are still getting exposed to it. If you’re still eating factory farmed food, you are getting exposed to all of the things that are making this difficult to overcome and override that metabolic inflexibility.

So first is become aware. Test, assess, address. Become aware for yourself. Audit yourself, audit your body care products. EWG also has a place to put in your body care products to evaluate, give them a grade. You don’t want to do anything below a B, you know, you want to get an A or a B on all of your body care and cleaning products. And so if you’re doing that, now you’re taking some of the burden out and those receptors and those cells start to, like, shake it off, right?

Then you want to make sure all of your emunctories are working, your organs of elimination. Are you sweating? Are you breathing well? Are you urinating well? Are you having your bowel movements well? Those are the things that help take the garbage out. If you’re backed up in any of those areas, those chemicals we just talked about can’t get out of the building. If anything, if you start to liberate them, you are actually recirculating them again and cause you more problems. So if you’re not eliminating well, you may just be recirculating, causing more problems. So that’s number two. You have to do that.

Number three, if you are someone who has a difficult time going more than a couple hours without food, if you have to have a snack at bedtime, if you have to get up in the middle of the night to eat, if you have to eat the second you get out of bed, if you get “hangry” or irritable when you skip a meal, you are metabolically broken.

The five other things to look for, which is how standard of care defines metabolic health, is a waist-to-hip ratio. You want your waist smaller than your hips. Okay, so there’s number one. Number two, you want your blood pressure 120 over 80 ideal, give or take a few points on either end, very close, without medication. You want your blood sugar fasting around 80 to 85 maximum, without medication. You want your lipid profile, you want to be in balance, you want to have your HDL, your good cholesterol up above 60 or 70 so that you know you’re methylating well, and you want your triglycerides down under 90 to know that your liver is not congealing all of that sugar-stored fat. Okay, that’s sugar-provoked fat storage, which leads to the fatty liver. And then number five is you want to make sure you’ve got good stamina, good energy, good vitality, and can actually be conditioned, like be able to take a nice walk, you know, be able to do these. Those are the five defining factors of metabolic health.

In 2018, a study from Chapel Hill, North Carolina, came out showing that Americans, which actually applies to all people living in Westernized environments around the world, but this was specific to Americans, that we as a collective, less than 12% of us are considered metabolically healthy.

David Stouder: Ouch.

Nasha Winters: Exactly, but it gets worse, David.

David Stouder: Oh, good.

Nasha Winters: Yeah, now for the good news! In July 2022, the American Heart Association came up with a follow-up study that shows that in fact, less than 6.8% of us are metabolically healthy. So here’s what I’m telling you. No matter what it looks like on the outside, even if you have a perfect waist to hip ratio, unless you’re really looking under the hood at certain labs, at some of those descriptors I just gave you, you are likely metabolically broken. You are actually the weirdo now if you’re not, versus, the exception to the rule. So you now know that pretty much everybody of 93% or better of us are walking around with some metabolic inflexibility that now hopefully you understand from the major changes we’ve made in the past 150-plus years, and especially since World War II, we’ve made it very challenging for any of us to achieve metabolic flexibility without more force.

David Stouder: Well, as we wrap up here, it seems to me, you say things like, a lot of people know, well, we eat too many carbs and we tend to gain weight or get a fatty liver, and we’re too sedentary, we don’t exercise, so we don’t burn calories. That’s different versions of how you apply that to your life. But what you’re saying, what I hear you saying is what’s really happening is that the kind of food, the garbage… I coined a phrase once: consumables radically absent phyto sustenance, or crap.

Nasha Winters: [ Laughs] Yes.

David Stouder: And well, the thing is, if you’re going to eat food and you’re just saying, oh, this doesn’t have preservatives, or this doesn’t have much sugar… you’ve got to get clean food, clean body care, and I say it this way to people. You don’t always have a choice. You don’t have a choice what air you breathe, right? But when you do have a choice, you make a good one. You have a choice what water you buy, what you put it in, what food you buy. So we don’t have to be overwhelmed, but can we just take steps, like cleaner produce and then cleaner this and cleaner that, and look at all your plastic containers, and start to get glass containers, and on and on. So you would advise people, don’t freak out and give up.

Nasha Winters: Right.

David Stouder: But step by step, clean yourself up, and then maybe your reduction in carbs and your exercise is really going to get you where you want to go

Nasha Winters: A hundred percent. So you start to pluck away. When you run out of one product in the house, replace it with something a little bit better. Same thing with your cupboard, replace it with something a little better. Your cookware, your dishware, your storage ware, your drinking water bottles, et cetera. If you want to make an investment, invest in a whole house water filter, or at least a sink water filter and an air filter. And then start to look at the basics of increasing your metabolic flexibility with the simplest things of fasting for 13 hours, meaning after dinner, do your best not to have anything until breakfast, 13 hours later. Most of us can’t do that. In fact, 93% of us can’t do that. But if you work towards it, maybe you can get six hours in. Great, start there. Eek towards it. Once you can master 13 hours with nothing but water, in that time between dinner and breakfast, you are already starting to reset some ancestral wisdom in your body.

So those are free, and it’s a starting point for everybody. Once you master that, you can work it up to 16 to 18 hours a couple times a week, up to 24 hours a couple times a month. And if you’re someone who’s trying to fight off a major chronic illness, work yourself up to 3 days of fasting a month. This is how our ancestors evolved. This is how we kept ourselves metabolically flexible. And then suddenly all those changes add up. It’s like putting money in your bank account.

David Stouder: That is excellent. You’ve really sort of opened up a great pathway for people, I think, who are struggling. And besides, I suggest everybody go back and look at some of our other podcasts we did with Dr. Nasha. Now is this your best website, www.DR, as in D R Nasha, N A S H A.com? Is that the best place for people?

Nasha Winters: Yes, start there, but as of a month from now, go to MTIH.org, which stands for Metabolic Terrain Institute of Health – you can put that in to get there – dot org, which is our nonprofit, which is all about the research, the network building and training physicians like this globally, the building of this hospital, and the building of the data platform to help everyone successfully create metabolic flexibility within their own lives to both treat and prevent chronic illness, including cancer.

David Stouder: Well, thank you so much. You know what, you have just brought a real breakthrough and put it on the table in front of all of us, and all we have to do is pick it up and use it – and I want to thank you. Thanks for being with us today.

Nasha Winters: Thanks, David and everybody else. All the best to you.